The first day of our tour was spent in Brisbane where we learn about the city’s role during the war. Thousands of soldiers and sailors as well as every type of supply you can imagine passed through Brisbane on their way to the battlefield. Essentially the military took any vacant space, vacant land, house, hospital, hotel, building, and pub. If the military wanted something they got it.

We had a local guide, Peter Dunn, who pretty much knew everything about Brisbane and the war. Driving out of the downtown area Peter would point to a building and say “that building was an American PX” or “ That building was the headquarters for the Seventh Infantry Battalion”. He showed us a park that, during the war, had 37 buildings constructed on it. It was the home for the Australian code breakers. Only one of the buildings was constructed of brick. It was where the IBM ciphering machines, used to break the Japanese codes, were located. They were too noisy to install in a wooden building. Peter took us a few blocks away to show us the beautiful house the code breakers were originally located. The ciphering machines were located in a garage behind the house but they made so much noise and the neighbors were complaining, and the building was way overcrowded, and it was a “Top Secret “ project so they moved the entire operation to the park. And yes, Peter showed us the building downtown that was the headquarters for the code breakers.

Our first stop of the day was a visit to what remains of the Eagle Farm Airfield. Built by the Americans, it was a critical airfield during WWII covering an area of 2.3 square miles. It was the wartime home of the 81st Air Depot Group. A previous airfield in the area closed due to the swampy conditions of the site. The Seabees (construction battalions) managed to elevate the site and create a suitable airfield. Interestingly, all runways in the Pacific Theater, both American and Japanese, were dirt runway often reinforced with Marston Mat.

Aircraft were assembled in the United States then disassembled, crated, and shipped to Brisbane where they were uncrated, reassembled, and test flown before flown out to a fighting unit. On an ongoing basis Allied engineers repaired, and maintained Allied aircraft at Eagle farm.

Today almost the entire site has been converted to an industrial park with three exceptions: 1. The Eagle Farm Museum. 2. A colonial era Women‘s Prison Site. 3. Hanger 7. The eagle Farm Museum is on the second floor of one of the buildings however in the entrance foyer there is a Cummings aircraft engine still sitting in its shipping crate base for over 80 years.

The museum on the second floor shows the history of the site from its colonial prison days through the Second World War. The prison was discovered when construction was being performed on a new building. They knew that there was a prison in the area but not exactly where. It started out as a men’s prison but when it became overcrowded the men were relocated to a larger men’s prison and the old prison became a women’s prison. When it was determined that they had discovered the women’s prison it was declared a protected archeological site. Minor excavations have been made and, for now, the site is a public park.

Hangar No. 7, was a secret project intended to give Allied aviators an advantage over the Japanese Zero fighters in particular as well as other Japanese attack aircraft. The Allied Technical Air Intelligence Unit, made up of personnel from the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, worked to rebuild and test recovered Japanese aircraft to identify their strengths and weaknesses. They would recover crashed Japanese aircraft, recover the undamaged parts, and build a composite aircraft. Over the skies of Brisbane, residents could occasionally see Japanese aircraft with an Allied escort or the aircraft painted in friendly colors to reduce the chance of friendly fire. To ensure the secrecy of the project, Hangar No. 7 stood away from the other hangars and operated under a tight security protocols. In attempting to rebuild the Japanese aircrafts they discovered that many of the parts were not interchangeable: wings from one Zero would not fit on another Zero. This told them that the Japanese aircrafts were, in essence, hand made. Considerable re-machining was required to build the new aircraft from existing parts.

After leaving Eagle Farm Airfield we passed two racetracks that were transformed into military encampments. There were an additional four racetracks in Brisbane that got the same treatment. We passed an open field where the allies stored chemical weapons. Yes, you read that correctly “chemical weapon “ and tons of them. They were never used during the war and were eventually dumped into the Pacific Ocean (thank you very much). Only African American soldiers were allowed to handle these weapons. They had no means to move around the site but local farmers, feeling sorry for the soldiers, gave them horses to use. Every place we passed seemed to be connected to the war effort in some way or another.

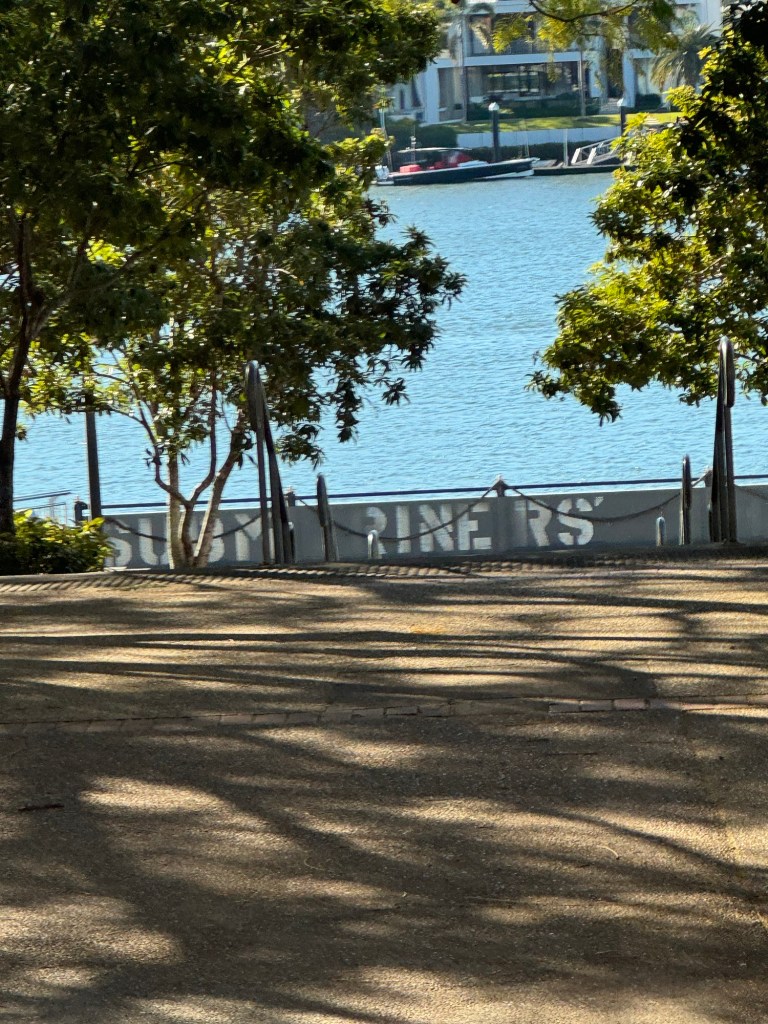

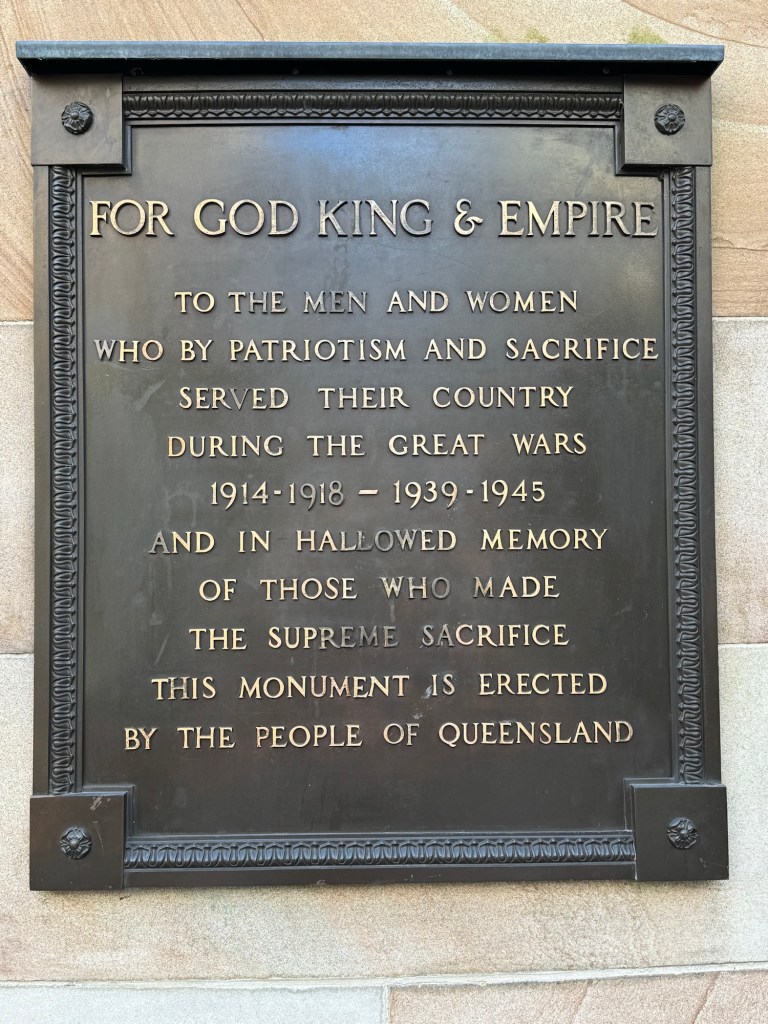

After lunch we stopped at the ANZAC (Australia and New Zealand Army Corps) Galleries. Opened in 1930, Anzac Square is the State war memorial of Queensland. It’s a significant public and historical site dedicated to the men and women who have served their country in conflict and peace since the Boer War.

Located in the Brisbane Central Business District, with the spectacular Shrine of Remembrance and Eternal Flame burning at its heart, Anzac Square provides permanent recognition for those who have served their nation and preserves their legacy by offering generations of Queenslanders a special space to reflect on their bravery and sacrifice.

Interesting fact – about 12,000 Australian women married American soldiers during the war. There were several “bride ships” that brought the new brides to the United States after the war, More often than you might think, the Australian brides met their husband’s American wife in the US and Re-boarded the ship for the return trip to Australia.

Leave a comment